Walking ‘Beyond the Heysen’ by Ray Hickman, accompanied and assisted on walks by Roger Kempson

Introduction

From where the Heysen Trail ends in Parachilna Gorge, the Flinders Ranges extend North through pastoral leases, conservation areas, Vulkathunha-Gammon Ranges National Park, Arkaroola Wilderness Sanctuary and the Indigenous Protected Area of Nantawarrina, to Mt Hopeless. The terrain is rugged, and many of the potential water sources are dependent on rainfall. For bushwalkers, this region of South Australia is both attractive and challenging, particularly for multi-day (pack-carrying) walkers. There are vehicle tracks that walkers can use, and traditional (marked-on-the ground) walking trails, with the latter located mainly inside the Vulkathunha-Gammon Ranges National Park and Arkaroola Sanctuary.

Previous walks

The best-known walking North of Parachilna Gorge was done by Warren Bonython who completed a walk from Parachilna Gorge to Mt Hopeless. An account of the walk is contained in his book ‘Walking the Flinders Ranges’. Bonython reached Mt Hopeless in November 1968 which meant that he completed his entire walk without the benefit of the 1:50,000 topographic maps that became available later. Consequently, the maps of the walk that Bonython was able to provide were rudimentary, but they specified well-defined points, and gave a description of the terrain between those points, that was sufficient to show that such walks could be done. Completing his walk assisted by such basic maps was, perhaps, the most impressive feature of Bonython’s achievement.

Another inspiring account of walks in the Northern Flinders has been provided by Adrian Heard in his book ‘A Walking Guide to the Northern Flinders Ranges’. This provides detailed accounts of paths he walked in the Gammon (Vulkathunha-Gammon) Ranges National Park and Arkaroola Sanctuary. The account of Heard’s walks, published in 1990, showed each walking path superimposed on topographic maps, along with grid references for important waypoints. Heard’s account made good use of mapping developments not available to Bonython. His grid references would have been obtained by matching physical features that he could see, from where he was standing, with map detail.

Parachilna Gorge to Mt Hopeless was just part of Bonython’s walk. It commenced further South at Crystal Brook and was the inspiration for the Heysen Trail which runs for 1200 km from Cape Jervis to Parachilna. The reason usually given for why the Heysen Trail does not go as far north as Bonython went is the cost, and difficulty, of establishing, and maintaining, a physical (marked-on- the-ground) trail beyond Parachilna Gorge.

There are others who have, like Bonython, gone ‘Beyond the Heysen’ all the way to Mt Hopeless. All these groups are exemplars of arid zone walkers, but one stands out from the others in an important respect. This is a group led by a former ABW member, Jeremy Carter.

In the period July 2009-April 2011 this group completed the walk and recorded the path as .gpx files. In this way they went further than any previous group in providing reliable guidance to other aspiring, arid lands walkers. Details of this walk, including the .gpx files, can be accessed by clicking here. Details of other Parachilna to Mt Hopeless walks are available at the same location. Carter’s Parachilna Gorge to Mt Hopeless walk was supplemented in 2012 by a walk he led from Mt Shanahan to Arkaroola. This walk involved a traverse of the Mawson Plateau which was not included in the earlier walk. A .gpx file, and highly readable account of this walk, can be accessed by clicking here

A walk in-progress

Adelaide Bushwalkers Club is in the process of recording, as a .gpx file, another ‘Beyond the Heysen’ path which will be quite different from that of Carter. This should further encourage and facilitate walking in the Northern Flinders Ranges.

Modern digital devices and bushwalking

The hand-held GPS and mobile phone have greatly increased the ability of bushwalkers to move safely through remote, rugged terrain without the need for a traditional walking trail, or vehicle track, to guide them. The .gpx files that these devices produce/utilise are at least as reliable as a trail marked on the ground. Walkers following a traditional trail can unintentionally depart from the trail and, when this happens, they can have difficulty finding it again. Getting back to a trail in the form of a .gpx file, after leaving it (whether intentionally or unintentionally), is more easily accomplished. It seems reasonable to expect that these devices, when they are used to supplement (not replace) traditional compass, and paper-map, navigation methods, will increase the number of walkers looking to walk in the Northern Flinders, and able to do so safely. Creating a trail in the form of a .gpx file has the additional advantages, over a traditional trail, of leaving no mark on the landscape, and no significant establishment or maintenance cost. Such trails allow walkers to meet the standard of ‘take nothing but photos, leave nothing but footprints’.

When navigation is by map and compass alone the navigator will have a topographic map and a set of waypoints through which they intend to pass. When reached, each waypoint is recognised by matching features seen at, or from, that point with features on the map. A grid reference for each waypoint can be recorded by reference to grid lines and numbers on the map. The record of walks where navigation was by map and compass will usually consist of grid references for key points, some verbal account of terrain, and a version of the map used with the key points marked on it.

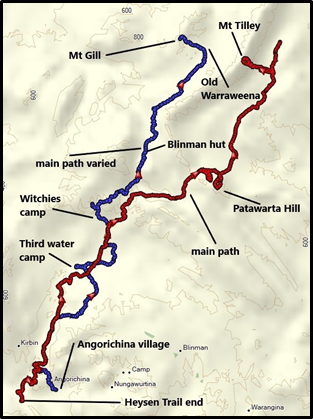

Figure1: Notional path (blue),

path actually walked (red)

If the navigator has a digital device capable of producing/utilising .gpx files then, prior to the walk, a ‘notional’ path, through a set of waypoints, can be loaded onto the device as a .gpx file. The device will display this path as a set of joined lines superimposed on a digital map. As the walk proceeds the device will display both the path actually walked and the notional path (see Figure 1). The navigator is able to determine at any time where the group actually is, compared to its notional path. If the group leaves the notional path, either intentionally or unintentionally, the digital device can be used to get back on course. When the walk has been completed there will be a .gpx file of the entire path actually followed and the file can be merged with topographic maps using Oziexplorer, Garmin Base Camp and other packages. This will facilitate the preparation of an account of the walk and may be useful to others interested in repeating the walk or something similar.

If the navigator has a digital device capable of producing/utilising .gpx files then, prior to the walk, a ‘notional’ path, through a set of waypoints, can be loaded onto the device as a .gpx file. The device will display this path as a set of joined lines superimposed on a digital map. As the walk proceeds the device will display both the path actually walked and the notional path (see Figure 1). The navigator is able to determine at any time where the group actually is, compared to its notional path. If the group leaves the notional path, either intentionally or unintentionally, the digital device can be used to get back on course. When the walk has been completed there will be a .gpx file of the entire path actually followed and the file can be merged with topographic maps using Oziexplorer, Garmin Base Camp and other packages. This will facilitate the preparation of an account of the walk and may be useful to others interested in repeating the walk or something similar.

Bushwalker access to pastoral land

Bushwalkers must have the prior agreement of the pastoral leaseholder to walk and/or camp on the lease, except where walking and camping will be entirely on a public access route. Any walking ‘Beyond the Heysen’ will involve very little walking on public access routes, there being only 5 such routes between Parachilna Gorge and Mt Hopeless. All 5 are south of the Copley to Arkaroola road and run mainly East-West. So, developing and promoting any ‘Beyond the Heysen’ walking will require the cooperation of pastoral leaseholders.

The Pastoral Land Management and Conservation Act 1989 does provide walkers with access to pastoral land subject to the leaseholder being informed of the walking plan beforehand. There is a right of the leaseholder to refuse access for reasons set out in Section 48(5) of the Act.

There is a long history of ABW members walking on pastoral properties of the Northern Flinders Ranges without coming into conflict with pastoral leaseholders. However, it would be quite understandable if a pastoral lease holder had concerns about bushwalkers moving off tracks into less accessible terrain. To help avoid difficulties of this sort, for its members wishing to do so, ABW might be able to make use of its reputation as an organisation which requires walks by its members to meet high standards of safety.

Day walking ‘Beyond the Heysen’

What follows now is a description of a set of day walks that Ray Hickman and Roger Kempson have done on three trips to the northern Flinders. The trips were private trips and the walks done made variations to the path recorded by Carter’s group, with the aim of the variations being:

- To reduce the amount of walking on vehicle tracks. In his book, on page 12, Bonython says ‘The ridge crest undulates only gently, and consequently it has been possible to grade a fire track along it for many miles. Although I wished the track were not there, for its existence spoiled the wilderness character of the landscape, I was glad to be able to use it because of my hard-pressed timetable.’ Here Bonython describes the main pro (relatively fast passage) and the main con (less of a wilderness experience) of walking on vehicle tracks.

- To make use of existing, for-hire infrastructure on pastoral properties and thereby provide some return for the pastoralist from the presence of bushwalkers on the property.

- To cater for all of day, overnight (light pack-carrying), and multi-day (full pack-carrying) walkers. For much of its length the Heysen trail runs through freehold properties and variations are few. But where it passes through parks that allow public access there are many examples of other trails that join and depart from it. This has produced a network of trails catering for a wide range of walking interests and abilities. Ray and Roger see digital devices and .gpx files as having the potential to create trail networks in the Northern Flinders.

Creation and manipulation of .gpx file

Figure 2: Carter path(red), variation(blue)

Creation of files: prior to each trip .gpx files for the intended (notional) walks were created in the Garmin Basecamp software and loaded onto a Garmin ETrex22x GPS device. From the start of each walk the file for the notional path was displayed on the GPS as a line of one colour and the path actually walked was recorded as a different colour (see Figure 1). As the walk proceeded we referred to the GPS and/or our paper map when we wanted to check that we were still on the right path. The GPS had been set to the same datum (AGD84) as the paper map.

Creation of files: prior to each trip .gpx files for the intended (notional) walks were created in the Garmin Basecamp software and loaded onto a Garmin ETrex22x GPS device. From the start of each walk the file for the notional path was displayed on the GPS as a line of one colour and the path actually walked was recorded as a different colour (see Figure 1). As the walk proceeded we referred to the GPS and/or our paper map when we wanted to check that we were still on the right path. The GPS had been set to the same datum (AGD84) as the paper map.

Manipulation of .gpx files: there are various ways in which .gpx files can be manipulated- these include joining files together, reversing them, splitting them at a selected point. The .gpx files that recorded our walks have been combined, by these means, with the .gpx file for the Carter path to create a variation of it. This is shown in Figure 2 where the Carter path is red and the variation to it is blue.

Variations on the Carter path

In the text from this point on the term ‘main path’ refers to the Carter path. Our variations to the main path are quite modest in terms of the distance recorded. We are describing them mainly with the thought that they might arouse the interest of other walkers who are thinking about doing, and/or leading walks, beyond Parachilna Gorge. Just as important as encouraging walks beyond Parachilna Gorge is the aim of encouraging navigation that makes use of digital devices.

An experienced walker, used to navigating with a map and compass only, does not need a digital device to successfully complete a walk. But they might see some advantage in recording their walks as .gpx files and using the files to prepare walk accounts for others to use. Less experienced walkers might see digital devices and .gpx files as confidence builders for attempts at walks more challenging than they have previously considered. Confidence in the value of this technology, and facility in use of it, can be established walking locally in familiar terrain.

Walks that vary the main path: in the Figures 3-5 below .gpx files have been merged with a topographic map using OziExplorer. All grid references are for the map datum AGD84. The red lines are sections from the .gpx file for the main path. The blue lines are .gpx files for the variations we recorded between Angorichina Village and Mt Gill on Warraweena. The green lines are .gpx files for sections that we intended to walk, and record, but did not. On our walks we always had in mind that two walkers of our ages (78+ years) needed to err on the side of caution when walking off-trail in remote terrain.

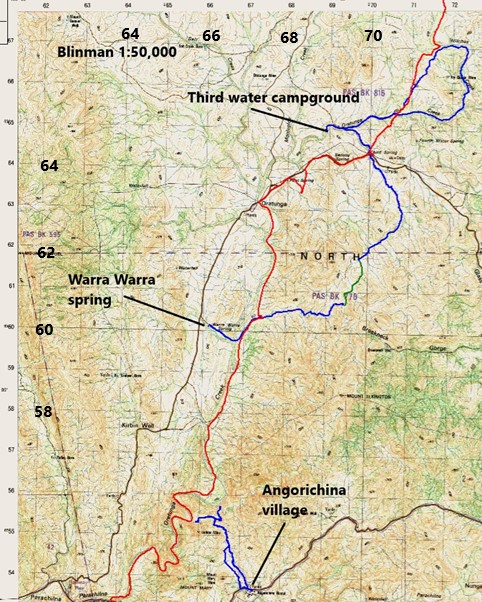

Walks from Angorichina, Warra Warra Spring, Third Water campground (Figure 3)

The main path begins a few kilometres west of Angorichina Village where the Heysen Trail ends in Parachilna Gorge. Our first variation started at the village. From here we walked a bit west of north into the Oratunga Creek. We followed a ridge going north from the village and then descended towards the Oratunga via a narrow creek that we entered at 666549. This led us into a tributary of the Oratunga at 664554. We first walked east along this tributary to the point 665557 with the thought that it might be possible to descend from there into the Oratunga to rejoin the main path. However, the terrain was too steep and we then followed the tributary back to where it joins the Oratunga at 658554. We retraced our path back to Angorichina Village via the small creek we had followed in. On emerging from that creek, instead of following the ridge we had walked in on we diverted a couple of hundred metres to the west and walked down a gentler slope that saw us walk onto the Blinman road a short distance west of the village.

Recording between Warra Warra Spring and Third Water campground was done on two out-and- back day walks. On one of these walks we went from the campground and on the other from our vehicle parked at Warra Warra Spring. For our walk from the campground we went southeast along the vehicle track shown on the Blinman Map as running from 693650 in the Oratunga Creek to Third Spring and the Glass Gorge Road. This track has largely disappeared through lack of use. From the Glass Gorge Road we continued southeast and then southwest to 697618. From this point we walked back to the campground. On our other walk from Warra Warra Spring we walked from the spring into the Oratunga Creek, followed it north, and then entered a substantial creek joining it from the east at 674603. We followed this to the point 694607 from where we returned to our vehicle. This left a gap between Third Water Campground and Warra Warra Spring that we did not record. This is shown in green in Figure 3. Views from either side of this gap indicated that it would be straightforward walking.

For another walk from Third Water Campground we went east along the Oratunga creek to where it is joined by Witches Creek at about 723656. We followed Witches Creek north then west to where the main path enters the creek. From there we completed a loop walk back to the campground.

Third Water campground has a long drop toilet and a simple shed where you can have a shower if you have a portable shower with you. The campground is about 4.5 km from the Homestead. The Moolooloo policy on hire of its campgrounds is that the hirer and their group will be the sole occupants.

Figure 3: Walks from Angorichina, Warra Warra Spring, Third Water campground

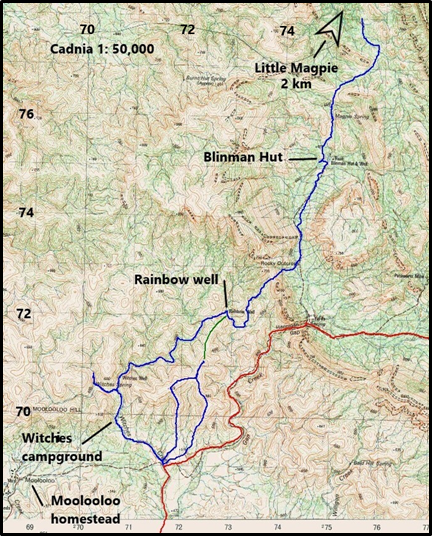

Walking from Witchies campground and Blinman Hut (Figure 4)

On a separate, and earlier, trip to Moolooloo we did some walking from Witchies campground, and from Blinman Hut. The relationship between the main path and our variations are shown in Figure 4. Witchies is about 4 km from the homestead on a 4WD track. The campground has a long drop toilet and water tank. Blinman Hut is 13 km from the homestead and the driving time is advertised as being an hour. It took us 1.5 hr but there were no sections of the track that were difficult to negotiate in Roger’s Pajero Sports. Blinman Hut has two flushable toilets and a shower, hand basin, kitchen sink and stove. For bushwalkers this is a 5-star campsite!

Walking from Witchies campground: our first walk was to Rainbow Well via Witches Creek, passing Witches Well along the way. Water was being pumped into a trough at Witches Well. The walk to Rainbow Well was pleasant and easy walking. The windmill, pipes, large tank and trough at Rainbow Well have been abandoned and the well itself is uncovered. We did a bit of wandering offline as we crossed the high ground from Witches Creek at 717691 to the Rainbow Well Creek. On reaching Rainbow Well we saved the .gpx file for the track walked and started recording a new track for the walk back. This time we walked up one small creek to a saddle and then down another small creek into Witches Creek. This was quicker than the way we had come in. On the way back to Witchies Campground we visited the spot where the Cadnia 1:50,000 map says there is a spring (Witches Spring). There was no surface water at this location or any sign of wetland vegetation.

Next day we walked from Witchies campground downstream to the Hannigan Gap vehicle track and the point where the main path joins it and follows it east through Hannigan and then Patawarta gaps. We retraced our steps back to 717691 where we ascended to the high point 679 at about 718706. On the way up this ridge we thought the ridge to the east had a gentler slope and decided to return via that ridge. We walked on to 724711 from where it is about 1 km down a gentle ridgeline to Rainbow Well. From here we walked back to Witchies Campground via the ridge that includes the high point 660 at 725704. In Figure 4 below the variation paths are shown in blue and the main path in red. The section not walked between 724711 and Rainbow Well is shown as a green line.

Figure 4: Walks from Witchies Campground and Blinman Hut

Walking from Blinman Hut: On one walk from the hut we walked north past Magpie Spring which is shown located at 749760 (Cadnia). There was no surface water at this location and no sign of wetland vegetation. After the Magpie Spring location, we walked another 5-600 m north to the saddle at 750765. Just below the saddle we walked onto an old vehicle track and followed it over the saddle. There was a fence line to our right and we allowed this to steer us down the slope which made for easy walking. From the saddle we went 1.5 km northeast and another 1 km northwest. We were aiming for a location beyond Little Magpie where both Mike Round and I had seen what looked like reliable water at 747801 on trips some years ago. On my trip we walked from Dunbar Hut on Warraweena to both Little Magpie and Magpie Water. There was no water at either location but we found water at 747801. On this day we turned back about 2 km south of this point, at 755780.

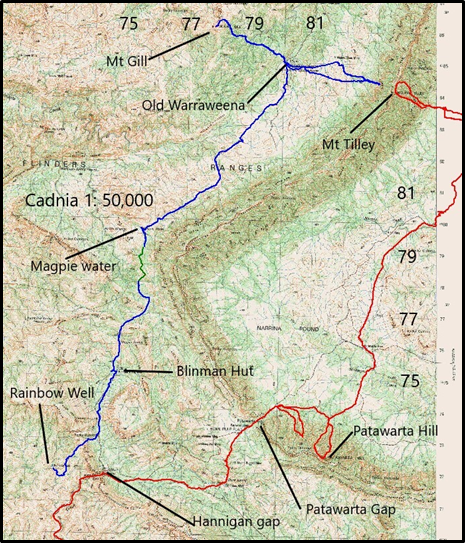

Walks from Old Warraweena (Figure 5)

On the telephone contact we made with Stoney Steiner prior to the walk he had advised us that he was no longer able to drop water at Old Warraweena and that there was no longer a long drop toilet located there. This was due to the difficulty of maintaining vehicle access from Warraweena. Stoney advised that the track was still driveable, with care, in a high clearance 4WD such as Roger’s Mitsubishi Pajero Sport. But the time now taken to get from the Warraweena headquarters to Old Warraweena made water drops and site maintenance there uneconomical. Our drive went smoothly enough but was quite slow illustrating what Stoney had told us.

Figure 5: Walks from Old Warraweena

Our first walk from Old Warraweena involved an unsuccessful attempt to reach the summit of Mt Tilley which is located about 3.5 km East of Old Warraweena. We ended up at 831844 with the ground in front too steep or us to proceed further. This was a reminder that digital devices using .gpx files are no guarantee of getting to an objective in the desired time. We could have backtracked and taken a longer route to the summit, over less steep terrain, but decided to turn around and go back to camp. Our main priority, for time spent at Old Warraweena, was to record walks from there South-West towards Blinman Hut and North-West to Mt Gill.

For our second walk we drove from Old Warraweena to 780821 where we commenced walking. Stoney had told us that our planned walking route would take us close to an old road. We did not see any clear sign of this in the form of marks on the ground, but we did walk some long sections where it looked as though trees had been cleared for a track. We aimed to walk to the point 755780 which we had reached on our walk North from Blinman Hut. We turned back at 791757. At Magpie water there was, as seen years earlier, no surface water.

The third walk from Old Warraweena was to Mt Gill and back. On the walk to Mt Gill, we approached the summit directly with the last section being quite steep. On the return we walked from the summit about 200 metres northeast on a vehicle track to commence our descent.

In conclusion

Recording any walk as a .gpx file only involves having a suitable digital device with you, switching it on when you start each day’s walk, then switching it off, and saving the file, when the day’s walk is concluded. The device used for the walks described above was a Garmin ETrex22x GPS. One pair of AA batteries will power the device for about 16 hours (2-3 days walking). The total weight of the GPS, and 4 spare batteries, is about 300 g.

It seems likely that most groups walking in the Northern Flinders these days would have a GPS with them. Many might only use it to check their position when that is in doubt, but no extra effort is required to record the entire day’s walk. When this is done the resulting .gpx file is something that will guide others as reliably as would a traditional trail without reducing the wilderness experience of walking in remote terrain. This gives the GPS the potential to do for walking in the northern Flinders something comparable to what the availability of 1:50,000 topographic maps did in the 1980s. If individuals and groups walking in the Northern Flinders do record their walks as .gpx files they can be collated and become a resource available to all. The Adelaide Bushwalkers Club is an organisation well placed to contribute to the development of such a resource.

Ray Hickman, May 2023

Comments (0)